The steps of forest growth and regeneration

Sustainable forestry is an important cornerstone in a bio-based society. We aim to keep creating growth for the future, because the forest belongs to us all. Here's how we manage the forest, step by step.

Seedlings and planting

Seedling production gives nature a helping hand and guides the tree through one of its most sensitive phases. Holmen cultivates seedlings at the nurseries of Friggesund and Gideå. Total capacity is just over 40 million seedlings per year.

Natural conditions at each site determines which tree species is chosen. For planting and direct seeding, this is pine, spruce or lodgepole pine. Holmen's land contains 50% pine, 30% spruce, 13% broadleaves and 7% lodgepole pine, calculated as percentage of standing volume. Pine and spruce are the most common trees in Sweden.

Planting is a robust method for forest regeneration, well suited to all climatic conditions. Soil preparation and planting should take place as soon as possible after harvesting in order to minimise the time with no tree cover.

But not every tree that grows is planted by us – far from it. Naturally regenerated seedlings of various species typically grow around the planted seedlings on the same site. This species mixture, with added genetic diversity to the target species, increases the biological diversity and resilience of the cultivated stands, concludes the Nordic Genetic Resource Center.

Thinning

Every tree needs light and nutrition to be healthy and grow well. Therefore, thinning is one of the most important activities in forestry.

Both pre-commercial thinning and commercial thinning involve reducing the number of stems in the forest so that the remaining trees can reach the proper dimensions. By thinning on several occasions, the most viable trees are selected and left to stand until the final harvest.

This action increases the future value of the timber by promoting growth among the highest quality trees. But, maybe even more importantly, it supports a higher ongoing growth in volume, which is necessary to maximize the carbon storage of CO2 from the atmosphere. We make sure that the trees, during all their lifetime, have good access to light and nutrition for optimal growth.

The mature forest

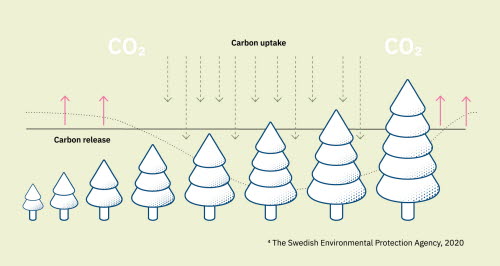

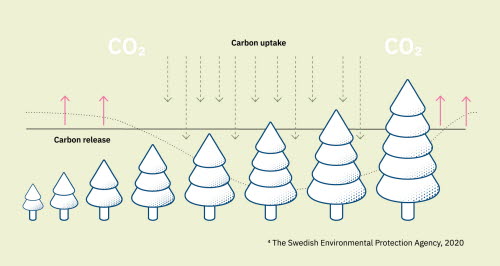

In the newly planted forest and at the thicket stage, more carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere than is captured by the seedlings. This is due to ongoing decomposition. But as trees grow, they capture more and more carbon dioxide. When trees are 20-40 years old, they have the largest carbon uptake in their lifetime.

This means that the maximum climate benefits occur in "middle-aged" forests, which in Sweden means at around 30-50 years of age. The annual growth of the trees peak; the trees will continue to grow after 40 years of age, but not as much and not in the same pace; the growth rate is slowly reclining. The net sequestration of carbon dioxide slowly reduces as the forest becomes mature. When the trees get very old, carbon uptake and release balance out, as decomposition again starts to take over.

When the trees are harvested in their mature stage, somewhere between 75 to 100 years of age, a greater carbon uptake can be achieved, since this will make room for a younger forest to continue the growth cycle.

It is important to maintain the circularity with care and responsibility for the natural, cultural and social assets of the forest. Reports show that unmanaged forests favour species that thrive in continuity, such as for example spruce at the expense of hardwoods, and disfavour species that needs change.

Set-asides and nature conservation to ensure a natural occurrence of dead wood and old-growth area development are important parts of the modern forest production for all species to thrive. But if the mature forest is left standing to grow old without being harvested, it will become more exposed to stormfalls, wild fires and forest pests such as bark beetle invasions. Responsible and active forest management keeps the forest vital and provides it with greater resilience.

Read more in the report from the Swedish Forest Industries.

Harvesting

A forest is usually not harvested until it is close to 90 years old. When it is time to harvest the mature forest, we reap the benefits of many people’s efforts throughout the forest’s life-cycle. Harvesting is the process that has the greatest impact on the forest landscape, but with good planning and care, the effects can be mitigated.

The waste is at a minimum. Actually, 100% of each harvested tree is used. The parts that cannot be used in industrial production – thin branches, roots and the spruce’s needles – stay in the forest and decompose. That way, they become natural nourishment for the ground and for the seedlings which will be planted after harvesting.

The main products from the fully-grown tree are planks and boards, where the carbon sequestered from the forest can be stored for decades, often hundreds or years and more. But planks and boards are square, and tree-trunks are round. So some parts of the trees become wood chips, which then becomes pulp. The slimmer, upper parts of the trees become pulp too, as well as trunks from thinning in the forest that are defected or not wide enough to become sawn timber. From this pulp we make paper and paperboard.

Regeneration

After the forest has been harvested, work begins as soon as possible on ensuring proper regeneration of the forest. This involves ensuring that seeds or seedlings survive and establish good growth.

For every tree we harvest we plant at least two – often three – new ones.

The future forest must provide a host of benefits and ecosystem services. It's like a cultivated work of art that is created jointly by many different people and by nature through complex relationships.